“One of the most significant mistakes made by observers of the technology industry's rise is to assume that the software produced by such companies is the reason for their domination of the modern economy. It is rather a set of cultural biases and practices and norms that make possible the production of such software, and thus are the underlying causes of the industry's success. The central insight of Silicon Valley was not merely to hire the best and brightest but to treat them as such, to allow them the flexibility and freedom and space to create.

The most effective software companies are artist colonies, filled with temperamental and talented souls. And it is their unwillingness to conform, to submit to power, that is often their most valuable instinct."

Alex Karp, The Technological Republic

Introduction

Starting a genuinely new company is akin to a creative act, and it is deeply difficult for many separate and combinatory reasons, practically, theoretically, and psychologically.

It’s true that someone shouldn’t start a company just to start a company. You should start a company if there’s a problem you want to solve in the world. There are many external problems I can see, but the most pressing problem I see is within myself. For me, the process of creating a company isn't a career choice but a test of identity.

As I log my own life experiences, it’s clear this isn’t about me. It’s about everyone in the world today. The world and its 8 billion people seems large and over-abstract and it can be difficult to find what makes you stand out. That difficulty is exactly why it is important to do. To not find your unique strength is to deny yourself and the world. If it is true for me, then it may be true for you. If it is important for me, then it may be important for you.

Chapter 1: Learned Weaknesses

My Struggle with Conformity

It has been difficult for me to conform and fit in my entire life. Early on, I was completely unable to follow the simplest instructions and rules. I feel dread with rules being imposed that I find difficult to articulate. But roughly, it approximates this concept I came across the other day.

“Psychological reactance theory, proposed by Jack Brehm, suggests that when people perceive a threat to their freedom, they become motivated to restore that freedom, potentially leading to behaviors that oppose the perceived restriction.”

Certainly this isn’t a feeling unique to me, but this is something that I feel in such an intense way that many cannot relate. To such an extent that someone doing something for me in a purely samaritan way threatens my individualism.

For much of my life, I resisted conformity while also needing to conform in order to progress through society. Existing systems reward reverence and punish irreverence. In order to get into a good college, you need to conform in high school. And then in college and jobs throughout my life, I faced similar challenges. In these environments, it always felt like I was destined for mediocrity as my heart was never in it. Seemingly, there was no alternative. Availability bias reduced my options to a menu of choices of college, classes, internships, and good careers. And of course, in these environments, I held a deep psychological reactance.

I must have an internally generated “why” in order to march forward. In the same way that it is much easier to write an essay in school on a topic you choose than an argument you are assigned, it is very difficult to fit into an existing, misaligned structure. I need to understand, believe in, and trust systems in order to work within them. If structure is imposed on me, or if I cannot see the big picture, I am crippled.

My hope is that this experience isn’t unique to me. And my hope is that my life is not destined to be a series of environments in which I fail to fit in. My final, last-ditch hope is that there is a place for me in this world, and that my greatest weakness, when flipped on its head, can be my greatest strength.

Thiel’s Contrarianism as a Beacon for Individualism

The world wants you to fit squarely into a box. This did not help my already innate inability to conform. In finance, I felt it at its most intense–a world defined by money, rigid structure, and blind execution. At around the same time, I read Peter Thiel’s Zero to One. This is packaged as a book on startups, but it is really an attack on the world we live in today with anecdotes on his similar experiences in law.

Thiel had the same feeling I did where he found competition at its most intense inside his first job at a prestigious law firm. He cites that “everyone on the outside was trying to get in and everyone on the inside was trying to get out,” picking at an odd nature of the competition that he fought so hard to win. He outlines his journey competing in school and college to get the most prestigious job and “win the competition,” only to win and then question what exactly he had won.

Conformity can lead to competition. This competition makes you better at the thing you are competing at, but it also causes us to lose sight of what it means to be individually human and provide value to the world. Surely, not every smart and ambitious person in the world is meant to be a lawyer, doctor, software engineer, or banker. Surely, in a world where there are an infinite number of ways to provide value, your unique strengths have a unique place. Surely, your worth isn’t defined by the number in your bank account. At the time, Thiel pushing the reader to ask “why” resonated with me deeply. As if after 22 years of life, someone just said out loud what I believed since I was a child.

Thiel had done quite well for himself by questioning convention. After reading the book, I saw a glimmer of hope that maybe my instincts against conformity aren’t simply a maladaptation.

Early Weaknesses

While I struggled to conform even in middle school, I also always had the seemingly odd realization that when I looked around at others in my class, no one was internally driven. Many seemed to accept what the world gave them without question. Few asked the very important question that I found so crippling in all my assignments, which was “why should I be doing this in the first place?”

If I examine my childhood deeper, this intrinsic motivation gave way to very odd individualism, where I would find myself going deep into things that others didn’t understand or care about. I studied more for chess than I did for school, and I refused to believe things others wanted me to believe.

I refused to adopt religion just because everyone around me did, as young as 7 years old. The rest of the children flowed through the local church system. They had to bring out the priests to try to convince me, and I refused to bow. My mind was incredibly stubborn without sufficient evidence. It is not easy, even as an adult today, to stand up against a crowd and refuse to follow the rules. This signal is something I weigh heavily when thinking about what makes me unique today.

In many ways, I was oblivious and stupid–a total space cadet. My mind was completely insulated from the outside world and most of my friends would easily poke fun at me for my social deafness and seeming inability to understand basic human interaction. Today, I am still an idiot when socializing.

I was very interested in technology, which was also very odd in the midwest. Over the years, I would notice a recurring theme in which a certain technological trend that I found interesting, or a certain business idea that I found promising, would years later blow up into the mainstream. There were no classes for this, but it was something that seemed somewhat natural to me. It was something that I could see that no one else could or cared to think about.

It was an even stronger signal that this was something I was drawn to in the midwest. The midwest is not like San Francisco, where young kids are steeped in technology from birth. It’s almost odd to not be interested in technology in San Francisco. The very fact that this signal was so uniquely strong for me in a technological desert emboldens my belief that it is unique to me.

Even when I was younger, I always felt a compulsion to follow these instincts of what I thought was interesting. However, the need to conform in school was always stronger. The desire to build something new that I thought was interesting was always too big of a sacrifice at the cost of not getting an A on a test or going to the event with friends. As a result of conformity, many important opportunities, and important learning experiences that would have shaped me no less, passed me by.

There are questions that this tension has forced me to confront over the last few years. Maybe my weakness is just a weakness. Or maybe, this maladaptation holds unique value.

Jazz “Blue Note”

I came across the concept of the blue note the other day, and I find it offers a helpful framing for how I am thinking about these questions. Alex Karp, who co-founded Palantir with Thiel and authored The Technological Republic, discusses his learned limitations and unique strengths with dyslexia.

“The advantage dyslexics have is, you know there’s certain things you should not be doing for a living. Most people don’t realize this.

I tell everyone internally—and everyone who wants to hear my words of great wisdom–at Palantir, everyone’s dyslexic. I’m the only person who knows it.

If you think you’re intelligent in all areas, it’s only because, in most areas, you haven’t met someone who’s really intelligent, and you’re deluding yourself.”

He discusses the importance of knowing your limitations, but also of knowing your unique talents.

“Jazz has a blue note. It’s a note that very few people can hear, and almost no one can play. Every world-class jazz musician can hear and play it, the people who produce jazz can hear it, but can’t play it.

To succeed in a profession, you will have to either be able to hear, or play, the blue note.”

Karp highlights early experiences struggling reading with dyslexia. By recognizing innate weaknesses, Karp is forced to confront them and to find what his unique competitive differentiation might be.

He ties this to Jazz’s blue note. You can not be a world class jazz musician if you can’t hear and play the blue note. Karp will never be world-class in domains where dyslexia cripples him. Karp recognizes his mind works in a different way than most people. However, similar to how blindness amplifies the sense of touch, he finds that this very neurostructural maladaptation makes him stronger in other domains.

What’s My Blue Note?

The lesson that I take away from this is that I will never be world-class in environments where conformity, structure, or convention dominate. I am simply crippled. This is my form of dyslexia and maybe I shouldn’t try to compete with the billions of other people who naturally fit in.

When Thiel asks us to question conformity, authority, and why we do the things we do, he sends us into the desert to find our unique path and “why.” When we’ve found our why, Karp similarly asks us to recognize our limitations and strengths and find our blue note and zone of genius to direct our focus.

The argument that I should go my own way only holds if there is another way that I’m better at. The point that I struggle with is whether there is a silver lining. I don’t find joy in being a misfit, as it has been a major weakness all of my life. The question that I am constantly looking deep within myself to unearth is what is my strength, if anything? What is my blue note? What can I be world-class at, if anything?

To be world-class at something, it has to be natural, like breathing. It has to be what you think about all the time. The best don’t leave their life at the door.

I’d like to believe that the inability to conform can be a strength. At this point, I see no other way–I keep hitting dead ends. And that exact reason is why this juncture of my life is so critical. I’m making a big bet that I can find my blue note and prove that I have something to bring to the table.

Chapter 2: Finding Your Blue Note

My quest here is just that. I feel it is important to give it my all to find my blue note. To not find it is to sentence myself to endless attempts at trying to be someone I can never be.

The Starving Artist and The Capitalist

There’s something inspiring about the starving artist. The starving artist is compelled to create, no matter the cost, and suffers worldly rejection in order to create for themselves. It is inspiring that the artist is willing to fail. It is inspiring that the artist and their work are inextricably bound.

On the other end of the same spectrum, I see the capitalist in the extreme. The capitalist denies his own humanity to accumulate capital and is rewarded by monetary validation. Where the artist’s motivation is intrinsic and intangible, the capitalist is driven by the ambition to capture extrinsically defined value.

Startups and technological innovation have the characteristics of art. “An inventor invents because he cannot help it,” Vannevar Bush tells us. There is a sense for me in which I feel compelled to create.

Across the scale of artists and capitalists, the technologist falls at some point in between. Art can have value too. Technology creates value by enabling the production of more with less. Technologists can be both the artist and the capitalist, if they can learn to capture that value.

Kafkaesque Fate of the Artist

Franz Kafka’s writing is profoundly depressing and in some ways captures the struggle of the artist. Kafka died nameless under the psychological shadow of his father. In his writing, anxiety and indeed psychological reactance seep through the words. Despite his writing today being recognized as brilliant and marking a generation, he lived his entire life feeling he was a failure for not living up to his father’s expectations. His father’s expectations for him to conform in the most shallow and narrow way possible in the insurance industry overlook the immense depths of Kafka’s mind.

Kafka’s work within insurance companies was not a reflection of his brilliance–Kafka never captured his value. His blue note remained hidden to the world. It was his unpublished writing, constrained by his environment, that made him world-class. He stands as a tragic example of the millions who have lived and died and never found their blue note. We have to imagine that in our over-structured world that wants to put us in a box, there is a place for us.

Failure to conform, mediocre conformity, and failure to find our blue note are all depressing ends. We need to find and capture our blue note, no matter the cost. Even with the existential importance of determining one’s greatness, most continue to fail to even ask themselves the question of where their very greatness may lie.

The Hard Thing

I knew that starting a company would be hard before taking the leap. However, that was all the more reason I needed to do it. The hard thing sharpens us, sets proper incentives, and possibly unearths our blue notes by embracing the infinite complexity of the world.

Incentives

Humans are optimization functions that optimize ourselves to a determined “why” or end. It matters to be purposeful in what we choose to optimize ourselves for.

In school and many companies, there is a certain level of skating by you can do. Consultants don’t own the business their consulting gets implemented in and don’t own the long-term repercussions of their consultation. While I’d like to believe they still put their best effort forward, they are driven to win business, they are not completely incentivized to provide value.

Engineering and mathematics are important disciplines in the very fact that there’s no shortcuts and the incentives are pure. Either the math checks out or it doesn’t. Either the code works or it doesn’t. Business has a similar nature. Either you make money or you don’t. Either your business functions or it fails. It is this exact proper incentive that I find to be important. Doing the hard thing forces you to optimize your character for doing hard things. If you go off the rails, there is no safety net. There is no one to save you. While it can be frightening to burn the boats, this is the way the real world works. Training wheels can only help you for so long until you need to jump into the deep end.

Nietzsche tells us, “when young men are ready to be sent out into the "desert," they are instead put into safe bureaucracies. They are "estranged from themselves" - the heat of their youth left cold. "Daily toil" becomes your opium and your edge is permanently blunted”.

Doing the hard thing sharpens the blade that is your human instincts. I believe this to be true so deeply that it feels to be a disservice to oneself and the world to do anything but the hard thing.

There is no harder thing than throwing yourself into the deep end and being forced to confront your weaknesses. Having to learn entire fields, create business ideas, find one that’s compelling, put the work in to understand the market and stakeholders around it, create clarity, learn to engineer, build the product, and finally sell it as a form of validation that you individually created real value from nothing. To do all of this in the wild is a powerful test of one’s capabilities. To fail, however, is an indictment of them.

Responsibility

When I started Nephra, and was the company’s CEO, there was a certain learning that was not fully present within the education system or in structured environments. In startups, outputs matter. Results matter. It doesn’t matter what you put in. In the education system, there are a fair amount of participation points that have corroded my perception of work.

Many people do some form of posturing in the world today. By saying all the “correct” things, perhaps you can even trick an investor into investing in you. However, you are only failing yourself in the long run. Raising money isn’t the goal, creating and capturing value is the goal.

Being CEO teaches you the importance of winning. No one wants to work for a losing team. There’s no participation points in the market. Even with the best employees, the responsibility ultimately falls on the shoulders of the CEO. It is immeasurably difficult and contained by no upper bound. But this difficulty, I believe, is the exact hard thing that we need to sharpen our animal spirits in a world that coddles us.

You should do the hard thing that sets the incentives to creating true value. You will learn to optimize yourself to that end. If you optimize yourself for bureaucracy and politics, you will have no choice but to become a politician. It should not matter who talks the loudest, what matters is value creation.

By optimizing our lives to solve hard problems with an unwavering focus on truth, we can save ourselves and the world.

Generality

We can think of our blue note as something we can see that others can not. It can be at some point along the infinite spectrum or some combination of disciplines, interests, etc.

Schopenhauer tells us “talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see.”

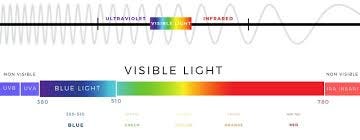

The importance of recognizing your limitations at 25 years old, where most of your brain is already developed, is you can start to get a feel for where on the spectrum that might be for you. Maybe your unique blue note falls somewhere on the blue light spectrum.

The problem arises in an over-structured academic or corporate context when you may go your entire life never being exposed to environments where you can make use of the unique neural pathways. Perhaps your job requires skills across the visible light spectrum. In this scenario, you will never find your blue note.

By eliminating all structure and exposing yourself to the entire spectrum of human possibilities, you may find you have a natural proclivity towards certain activities. You may notice that you have particular aptitudes that you didn’t know existed. You may connect dots that others cannot even see. It is only by embracing the complexity of the world that you can start to suss out the unique lens in which you view it.

By removing yourself from a narrow box and plunging yourself into the infinite complexity that is the real world, you are able to use the full power of your human brain to form novel connections that only you see.

The Rorschach test, or inkblot test, is a projective psychological test where subjects describe what they see in a series of inkblots, and the responses are analyzed to assess personality characteristics and emotional functioning.

If I placed a simple picture of a chair in front of you, everyone would see the chair. However, as you increase complexity and ambiguity, one interpretation becomes 1,000,000 possible interpretations. Your unique lens on how you see the world is a projection of your mind. The way in which your brain uniquely connects these data points is unique to you. You can learn a lot about a person, and even yourself, from what you write or see.

Take a step back, remove yourself from any invisible perceived notions of what is acceptable and what box you feel you should be in. Only by removing yourself from the box and letting yourself wander can you find what your unique strengths may be.

Finding My Blue Note

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what your blue note is. But I’m gathering some intuition on what it is for me. I can find examples where I see things others don’t.

I feel that I have a gift in my taste for business, technology, and people. I don’t even think these are random, they are things I’ve been very focused on all my life. It’s hard to have a good taste of each in isolation but the combination of the three feels very powerful if you can muster it.

While it is great to have good sense for ideas and people, that’s really not enough. Many people can have great ideas. There is so much more that goes into these things. Creating something genuinely novel requires dipping into chaos and rising from the ashes, and ultimately executing upon said creation. It requires conviction and being able to hold something in your head that others don’t see. It requires the same stomach that an investor has before making a big bet but also with the actual hard work over months or years to make it a reality amidst all the doubt. It requires the aptitude to actually build the damn thing. There is so much that comes after that initial gift that has to be learned through trial and error.

If there is anything I’d like to be world-class at, it is this creation, execution, and coordination of people, capital, and ideas that I find powerful to enact the most change in the world. Money runs the world, technology changes it, and people ultimately direct that change.

I write a lot today, but I never wrote in school. Writing never made sense to me when it is a form of simply fitting into structure. Now that I see it as a way to think through problems, ask out-of-distribution questions, create meaning from chaos, I find that there’s something about it that is tied to my blue note. I find much of my writing is deeply introspective. Much of my writing asks questions that I’d like to understand about the world, technology, business, and culture. Much of my writing leads to non-linear realizations that solve problems. It is this process of asking questions, wrestling with problems, and sussing out answers that feels natural to me, yet so few people in the world engage with. In a world where no one questions anything, perhaps it can be a strength to question everything.

Writing is also a projection of the mind. Everyone thinks in their own unique way. The most personally rewarding practice I have taken up is not only writing but also examining my past writing for subconscious themes and patterns that reveal more about what makes me unique.

My process is usually learning about something that I find interesting or important. Many of these things never pan out. But once in a while, I’ll get hit with a lightning bolt of inspiration and feel a sense of mania where a discovery excites me so much. This is the same feeling I had when I was younger about new ideas, gathering people, and starting new organizations. Over time, the sensation has become more refined, and I’ve become relatively numb to the oscillations in mood associated with it. I now recognize that the idea is something to pull on, but that it’s just one of many steps. There still is no better feeling than this act of creativity, revelation, and instinct.

It is this insulated curiosity and discovery, questioning systems and creating new things, creating clarity around a vision, and showing others what can be that I feel can be my blue note.

Others’ Blue Notes

In 2022, I ran an experiment asking people “why” they do the things they do, only to find damning evidence that few really know why they do anything, including myself. I ran a similar experiment asking people what their “blue note” is now in 2025 only to find similar results. How can we expect ourselves to be great if we don’t ask ourselves what we’re great at or have a guiding belief system and “why?”

I’ve asked myself these questions my entire life. As I ask myself what makes me stand out, I’ve found at times it is the very fact that I ask the question to sometimes be the most important differentiation. The world is already very complex. Our minds are also complex. But to only explore the complexity of one or the other leads us astray.

You should not only have a logical “descriptive” understanding of the world but also a clear “normative” belief system for how the world should be.

Finding your “why” and forging your belief system is half the battle. After you find your “why” and guiding vision to life, you need to think for yourself to unearth and protect your unique talents and blue note, while recognizing your weaknesses and limitations, to execute and shape the world.

The Existential Question

But as I take my life into my own hands in search of my blue note, the measure of success, however ambiguous, has become more critical.

For me to organize my life in a way that my work and beliefs are the central component, and my work and identity are inextricably bound as the artist, failure becomes existential.

If my life has been a series of me failing to fit in, with entrepreneurship being a last-ditch attempt to find my blue note, only for me to fail, then all has been for naught and the very point I am aiming to prove to myself can be debunked.

If you believe in yourself and take a shot, then you shouldn’t miss. The rest of this essay will lay out the 3-part logical proof (external, theoretical, and practical) that I am using to close the loop on hitting my mark.

If I do hit my mark, then the indictment is not of my identity, but rather an indictment of our society.

Why did it take me 25 years to realize this? Why did no institution in the world support questioning? Why does everyone seem to be locked in boxes that they don’t even understand? Why do we all receive the same structured curriculum? Why doesn’t our culture reward individual thought? These seem trivial but we should be frustrated with both the world and ourselves.

Chapter 3: External Proof

So far, I’ve laid out my struggle with conformity and looming questions of whether I have a place in this world and whether or not I am wrong to question conformity. Then, I’ve drawn thinner lines in the sand for what I feel may be my blue note.

In this chapter, I aim to close the first part of the logical proof that I am not misguided in my irreverence towards conformity, and that my inability to conform may actually be my strongest instinct.

I will draw parallels between my own writing and Karp’s attack on American culture. You will see that they are near reflections. As with many things, when I initially wrote these snippets, they were not even targeted towards any specific institutions. They were simply an isolated exercise of me logging my individual beliefs, which always feels heretical in the moment.

My Instincts

Thinking about society today, at the level of the individual and the abstract cultural level, it seemed so clear to me from youth that there was simply a lack of questioning. A lack of intrinsic desire. I clung on to the writings of Thiel that empowered my belief system that something was off. Each time I made a decision based on my belief system, it felt discouraged in the moment, but over time, it is those paths less traveled that were the most important decisions. In banking, where it felt like I had won the competition put forth by the world that others so desired, I found it personally empty inside.

I notice cultural problems everywhere I go. Few think for themselves. No one questions anything. Questioning isn’t supported by the modern, over-structured systems built for stability. This was the inspiration for Irreverent Capital. In a world that changes so fast, and what was true yesterday is not always true today, that gives way to endless opportunities for creating new and improved things, we need to rethink the world. We need to question everything.

Irreverent Capital

I started Irreverent Capital with a long-term goal of shifting American culture. This is undoubtedly a large feat, but I find it incredibly important to do. It seemed that the problems we face as a nation are cultural. Everything is downstream of culture (Culture). If you can fix the culture, everything else will fall into place.

Many of these are descriptive and normative statements that are driven by my experiences over the last 25 years.

“Startups have taught me that culture is critical. Values such as irreverence, curiosity, agency, and industriousness are necessary to challenge the status quo. While the demand for new solutions remains high, the supply of innovators and courage is relatively low. Irreverent will build upon this inefficiency.”

Culture is just a grouping of individuals. It seemed to me that the solution was that each person necessarily has to choose to strive for individual greatness and solve important problems.

The future must be pioneered by everyday citizens individually choosing to solve important problems. Richard Hamming of Bell Labs asks us,

"What's the most important problem in your field right now? How come you're not working on it?"

It seems true that the United States faces many problems, yet ambitious people are clumped into entrenched institutions that don’t solve them, at a time when technology enables us to question, and improve, everything.

“In 2024, The United States faces many challenges, including a lagging military-industrial complex and rising geopolitical conflict, difficulty finding skilled labor, and the continued lack of understanding of the human condition.

On a more optimistic note, technological advancements today enable us to solve more problems than ever before. New solutions can be created daily and much of the world will look incredibly different 5, 10, and 50 years from now as the impact of technology grows exponentially.”

“The main lever for progress in an industrial society is technical innovation. However, many ambitious people are working on problems that don’t move the needle for the next generation or are working within likely, structured systems that don’t innovate.”

There are two major components to this bottleneck, after people choose to solve important problems:

Aptitude

Attitude

Many experiences have shown me that there are many people with ideas but there are few people who actually build them.

Doing new things is not only hard because engineering is hard–there is a psychological component. It requires rejecting society. It requires questioning existing systems. And in many cases, society is structured to punish you for this. At its core, innovation requires irreverence, an unnatural instinct in the face of evolution, but a virtue that we need to destigmatize in order to progress as a society.

The bottleneck of progress is hard work, agency, and great engineering.

“If the culture is heavily infused with respect and worship of ancient wisdom so that any intellectual innovation is considered deviant and blasphemous, technological creativity will be similarly constrained. Irreverence is a key to progress” - Joel Mokyr, A Culture of Growth

Thiel tells us, “brilliant thinking is rare, but courage is in even shorter supply than genius.” - Zero to One

These are big asks of people. They are not easy. The salary isn’t as good as working for Google or Goldman Sachs or Latham & Watkins, but I believe deeply that they are important and more meaningful. We need to recognize money is only a proxy for value and disentangle value from the market. Our most valuable resource, our own human focus, is currently allocated towards imperfect market incentives.

Confirmed Instincts

I was looking forward to the release of The Technological Republic by Alex Karp for some time. The summary of the book goes as follows.

Our most brilliant engineering minds once collaborated with the government to advance world-changing technologies. Their efforts secured the West’s dominant place in the geopolitical order. But that relationship has now eroded, with perilous repercussions. Today, the market rewards shallow engagement with the potential of technology. Engineers and founders build photo-sharing apps and marketing algorithms, unwittingly becoming vessels for the ambitions of others. This complacency has spread into academia, politics, and the boardroom. The result? An entire generation for whom the narrow-minded pursuit of the demands of a late capitalist economy has become their calling.

The rough overview of the book captured my experience in banking, where you felt like you were just another cog oiling the machine, with thousands waiting to take your place on the Titanic. It calls out the U.S. for a lack of a belief system. It highlights Silicon Valley as a powerful culture that has accomplished great things, but that the market similarly incentivizes building targeted consumer applications that 1) aren’t authentically novel and 2) aren’t important. He urges the west, in this great moment of political and technological importance, to recognize what it is about Silicon Valley that is powerful, and calls for us to think deeply about what problems to solve and how to allocate our great gifts as humans towards work that matters.

A Cultural Solution

I called out the need for cultural change and great engineering. In this book, Karp does too. Karp tells the onlookers who watch from afar how Silicon Valley continues to churn out great innovations to think deeper about what is powerful about the valley. At its core, the valley is a counter-cultural movement that flies in the face of an over-structured corporate America.

The problem isn’t only that people are no longer individualist, Silicon Valley has retained this feature of its greatness, which largely empowers individuals to harness their creativity, rather than over-centralized planning. However, hyper-individualism, I believe, is isolated in the means by which the market dictates the end.

The major shift that needs to occur is individuals need to think for themselves about the actual problems they are solving in the world. In many cases, this requires a departure from individualism and for people to think about what collective identity we hold as a nation. What problems do the collective face? We have good enough photo-sharing applications. We do not, however, have enough people curing cancer and building up the very military-industrial complex that protects our freedom to create.

“The legions who have flocked to Silicon Valley are cultural exiles. They have consciously chosen to remove themselves from capitalism’s dominant corporate form and join an alternative model.”

Non-Conformity as a Virtue

Here is the most important passage in the book for me. It is the very non-conformity and instinctual irreverence that powers the great innovations of Silicon Valley. This is not a defect but the central feature of human creativity. It is not just the aptitude of the valley that gives it its power, it is the attitude.

"We have over the past century essentially cast culture aside, dismissing it as overly specific and exclusionary. But in Silicon Valley–even as many have neglected national interests—a set of cultural practices has proven so generative of value, that we ought to take them seriously, and particularly as ideas that might provide a basis for rethinking our approach to government, and the provision of public services. Why should the private sector alone be the one to benefit? Many seem to be watching the rise of Silicon Valley at a distance, eager, of course, to make use of the contraptions and services that it has produced and occasionally indignant at the industry's concentration of power, but essentially observing from afar. Where is the desire and urgency to co-opt and incorporate the cultural values that are the precondition for what the Valley has been able to build?

One of the most significant mistakes made by observers of the technology industry's rise is to assume that the software produced by such companies is the reason for their domination of the modern economy. It is rather a set of cultural biases and practices and norms that make possible the production of such software, and thus are the underlying causes of the industry's success. The central insight of Silicon Valley was not merely to hire the best and brightest but to treat them as such, to allow them the flexibility and freedom and space to create.

“The most effective software companies are artist colonies, filled with temperamental and talented souls. And it is their unwillingness to conform, to submit to power, that is often their most valuable instinct."

It is this irreverence that powers the future. People need to recognize this. The next chapter calls out how obedience, the innate human need to conform, can often be our biggest weakness.

“The instinct toward obedience can be lethal to an attempt to construct a disruptive organization, from a political movement to an artistic school to a technology startup.”

“Our desire to conform is crippling when it comes to creative output. It is this insensitivity to a certain type of social calculation, and the resistance to conformity, that has been essential to the rise of Silicon Valley’s engineering culture.”

“The modern enterprise is too quick to avoid such friction. We have today privileged a kind of ease in corporate life, a culture of agreeableness that can move institutions away, not toward, creative output.”

“The artist and the founder alike are often the mad ones. The challenge, of course, is that some of the most compelling and authentic nonconformists, the artists and iconoclasts, make for notoriously difficult colleagues.”

Conformity as a Defect of the Human Condition

We are attuned to doing what’s normal. We are attuned to fitting in. This is not what innovation requires.

“René Girard observed the conflicts and rivalries between monkeys that arise when one member within a group selects a single banana out of many, all of which are identical.

'There is nothing special about the disputed banana,' Girard said in an interview in 1983, 'except that the first to choose selected it, and this initial selection, however casual, triggered a chain reaction of mimetic desire that made that one banana seem preferable to all others.'

Our earliest encounters with learning are through mimicry. But at some point, that mimicry becomes toxic to creativity. Some never make the transition from a sort of creative infancy. Much of what passes for innovation in Silicon Valley is, of course, something less—more an attempt to replicate what has worked or at least was perceived to have worked in the past. This mimicry can sometimes yield fruit. But more often than not it is derivative and retrograde.”

“The act of rebellion that involves building something from nothing—whether it is a poem from a blank page, a painting from a canvas, or software code on a screen—by definition requires a rejection of what has come before. It involves the bracing conclusion that something new is necessary. The hubris involved in the act of creation—that determination that all that has been produced to date, the sum product of humanity's output, is not precisely what ought or needs to be built at a given moment—is present within every founder or artist.”

Too few of the many misguided souls flooding into banking and law are doing new things. Similarly, when I walk around Silicon Valley today, many people's work is not actually doing something new.

My Passage: The Information Theory of Startups

There is a Need for More Unlikely Things

“There is no value in doing new things for the sake of doing new things, but it is my observation that the vast majority of people in the world are not doing new things. And some of the people I saw doing new things in school and SF were seemingly doing new things because they like the idea of doing new things.

‘At a time when the growth of useful knowledge is expanding exponentially, which leads to increased opportunities for growth, society has bred citizens who aren’t irreverent or hard working enough to pursue them.’

Even in silicon valley, there aren’t enough people doing that much new stuff. Humans are the most sheep-like, domesticated animal of them all. There are more problems that need to be solved than people to solve them at this moment. Many of the AI companies are solving the same exact problem.

The observation I also had from UIUC is that many students were chomping at the bit to join exciting “new” things, but most people don’t themselves start them. If that is the case, it feels like my moral obligation to tackle the initial curve of hard problems. Vannevar Bush highlights the need for far-seeing and energetic individuals in advancing technological progress.”

Cultural Comfort and Decay

Corporate America, in its over-structured, and over-centralized culture, suppresses these very instincts that Silicon Valley has so effectively harnessed.

When I talk to my friends, they are always dumbfounded how much of the employees in their company are lemons that provide zero value and don’t actually do anything. When you put 2 and 2 together, you realize that the entire world is like this.

The incentives are off. People are too comfortable. Salaries are domesticating. People are working inhuman, overly structured, uncreative jobs. If they are ambitious, they are working jobs that don’t solve new problems with no equity and no responsibility, slotted into ever-narrower roles, and are pursuing the ambitions of their owners. They aren’t questioning where this all ends. (Reflections on a Quarter Century of Life).

Hierarchical structures with invisible pecking orders that suppress the best ideas and people from rising to the top dominate. This has incentivized jockeying for positions rather than creating value and the gross misallocation of human focus. When you look around, do you find that others are engaged? 79% of employees are unengaged at work according to Fortune.

The proper corporate structure, according to Karp, more closely resembles a honeybee swarm, without an overbearing and unnecessarily centralized mechanism of control, where individuals at the brim are experts in their blue note given the freedom and responsibility to harness their creative brilliance. This structure is in many ways the most essential feature of a successful startup and engineering culture.

The Improvisational Startup

The reason startups are hard and creating new things is hard is that it is inherently improvisation and dynamic, guided by human instinct rather than a perfect business plan. This is the exact opposite of what we are taught in school and in static institutions. Karp outlines this as:

“The parallels, however, between improvisational theater and the plunge into the abyss that is founding or working at a startup are numerous. To expose oneself on the stage, and to inhabit a character, require an embrace of serendipity and a level of psychological flexibility that are essential in building and navigating the growth of a company that seeks to serve a new market, and indeed participate in the creation of that market, rather than merely accommodate the needs and demands of existing ones.”

“Jerry Seinfeld has said, ‘In comedy, you do anything that you think might work. Anything.’ The same is true in tech. The construction of software and technology is an observational art and science, not a theoretical one. One needs to constantly abandon perceived notions of what ought to work in favor of what does work.”

The importance of engineering is that it is the process of taking theory that the high-church theologians praise and actually implementing it to work. If you are narrowly siloed in the world of ideas, your blind spots are too great. If you act only in the world or only separate from it, you can’t improvise to make something work. You need to straddle the line between many opposing forces to dip into chaos, give birth to a shining star, and translate it to the rest of humanity (Structure, People, and Chaos).

Validating Your Note

Where Thiel validated my instinct to find value in places more meaningful to me and unearth my “why,” I still found myself searching. Every system that I trust my instincts in seems to hate me. What Karp does for me is closes the loop. It is not enough to reject or get rejected by a system. You need to have a valuable, firm belief system, find your blue note, and embrace irreverence unapologetically.

As an individual, you need to fight for yourself in this world or find people you trust. Your instincts have value, and if you don’t capture that value, then someone else will. If it is true that individuals need to fight for themselves in this world, then Karp is right that cultures need to fight for themselves too. Both individuals and the west itself needs to take a step back and think about what makes us great, and stop at nothing to protect and harness those instincts.

In my wariness to embrace my own instincts, Karp offers validation that I am not completely alone in trusting them. And that those instincts, however disastrous they have been my entire life, can actually be my greatest strength.

While Karp’s external validation is helpful, this remains a hypothesis to be proven. I must prove it theoretically and practically.

Chapter 4: Theoretical Proof

Another angle to look at this problem of human instincts is theoretical.

If I was trying to write this segment 5 years ago, I’m not sure where I would even start. What makes humans unique within the power of the 86 billion neurons of the human mind is desperately complex. However, we can actually gain some insight into what makes humans special by understanding exactly what it is that we can do better than increasingly intelligent machines.

Furthermore, as deep learning capabilities exponentially increase every year, this adds another layer of existential importance to our quest of finding our unique human strengths. Not only do we need to understand how we can escape blind competition in this world, we need to run away from practices that are easily dominated by computers.

“Human focus is the most misallocated resource on planet earth.”

“If competition is for losers, repetition is for computers.”

The bad news is that it becomes harder to find our blue note. The good news is that when we find it, and have access to intelligence in the limit, we will find incredible leverage in our uniquely powerful human creativity for the decades to come.

The importance of this section is simple.

As an individual, you have powerful human instincts.

Those instincts are best allocated towards doing new, original, creative, unlikely work with your unique blue note. This inherently requires going against the grain and where there is no data.

As the world transitions to one where likely and existing things have no alpha, the value will be in harnessing your unique creativity to create new, unlikely things. This process can be mathematically defined.

Knowing Your Strengths in the Age of AI

It is more important now than before to uncover what your blue note is. What large language models do is they commodify anything that's not original. So your core value proposition is going to be what you do that's culturally or individually particular. It is your blue note that has value. These models are trained on anything and everything that already exists. So if it exists, it’s known and there’s little value.

You should work in your zones of brilliance, where you are the most adept. Areas where there is sparse data and you can make sense of it to create new things. Then you should direct those talents towards solving valuable and important problems for the world.

Creative genius is more important than ever. What AI does is it maps complexity. It does this by training on data that already exists. Humans still stand above machines in our ability to navigate complexity with limited data and live our lives by our own belief systems.

What the blue note signifies is something that you can see that others can’t. It’s something you understand about the world that others don’t. It’s what you are uniquely interested in. It’s what you are uniquely good at. To fail to find this for yourself is to deny yourself the very instincts that make you human.

And you do have unique instincts. People who over-emphasize pedigree and education and IQ are fiddling at the margins. Anyone with a human brain holds immense power within. You just need to unearth it from yourself.

Formalized Logic

In this logical proof, Politzki’s Law and the Human Focus Optimization Theory (HFOT) represent the power of the individual and the power of irreverence, respectively. Politzki’s Law necessarily shows you that if you have a human brain, you already have incredible leverage and powerful instincts in your ability to think for yourself. HFOT tells you that your alpha is in directing those instincts towards new value in domains where you are uniquely adept.

Politzki’s Law

Politzki’s Law states that when problems become more complex and have less available data, humans gain an advantage over machines. In domains with high complexity and limited data, human creativity and intuition outperform computational approaches. Consider three variables that shape whether a problem is best suited for human or machine problem-solvers:

C (Complexity): The dimensionality, ambiguity, and openness of the problem space.

D (Data Availability): The amount of reliable, relevant information available.

G (Generalization Factor): The ability to apply insights and solutions across domains. G is not an independent variable but a function of how well the problem solver—human or machine—can handle differences in C and D.

Where complexity (C) is high and data (D) is low, humans dominate. Our capacity for holistic thinking, pattern recognition in foggy, unclear environments, and reimagining constraints gives us an edge. On the other hand, when data is abundant and complexity is more manageable, machines can optimize solutions at scale.

Practical Implications:

To leverage your uniquely human strengths, seek out domains of high complexity and limited data. Focus on challenges that defy easy pattern-matching, where human insight and adaptability are essential.

Human Focus Optimization Theory (HFOT)

Knowing this is only step 1. In order to maximize YOUR unique instincts and blue note, you have to understand yourself, which brings us to the HFOT.

If we hold Politzki’s Law to be true, then it matters that people are working on complex ambiguous problems to maximize leverage of the population. However, that isn’t always the case. Many people are working in process-oriented roles, factory lines, or in repetitive environments that don’t create novel, useful things that move the needle for the next generation.

We may even be able to come to some agreement on what the most complex problems are that have the least amount of data, however, it also matters that people are solving different novel and unlikely problems and focusing in different directions.

The question we can ask ourselves is what would not get done “but for” you. What important problem is no one working on? What do you understand and believe and are uniquely interested in?

Humans should run away from competition and repetition in order to provide the maximum utility to the world. This requires self-understanding, thinking critically for oneself, and maximizing the impact of your human instincts.

The Proof

I had written this at the time as a way to formalize my own beliefs. In a world where computers aren’t able to handle generality and complexity, you still stand above them. So what do you spend your powerful and scarce human focus on?

Karp affirms my irreverence towards existing structure

Politzki’s Law and the HFOT logically found my argument that existing structures become commodified with increasing intelligence. The point is that as an individual, you have powerful unique instincts and that those instincts should be used on the edges of society with an attitude of improvisational exploration, where there is little data, and you can solve new, unlikely problems.

Irreverent is a case study of me actually executing upon this proof in practice. Going from zero to one. Going from chaos to product and customers. Once this customer validation is complete, I will have closed the proof and validated individualism, irreverence, and indeed my own identity.

In the intelligence age, corporate structures will either be commoditized and automated or need complete reinvention. Either way, it opens up endless engineering opportunities for people with freed up focus.

With this proof in hand, I’d like to invite others to join me. The consequences of where you spend your focus are not trivial. Your instincts are powerful and you should treat them as such to maximize the impact of them to create and then retain the maximum amount of value possible.

Chapter 5: Real-Life Proof

What I’ve described above is an overview of my journey to the exact moment that I type out this sentence. While it’s easy to make it seem like this was all a grand plan, it was not. You can only connect the dots looking backwards. The only reason I found any of this was through disengagement with the external world, rejecting conventional rules, and simply letting my instincts guide me.

So any reader cannot necessarily repeat this path–I’m not even sure I could repeat this path. It has been completely improvisational. So with that said, I am going to write this passage from a purely objective and descriptive view. Writing is linear, but this path was not linear. Perhaps later, I will tie this into a grand narrative, but it was certainly not that in the moment.

Prehistory

In college, I began writing to make sense of the world, similar to this essay. At the end of 2023, I found incredible personal value in a new exercise. I started re-reading old writings and uncovering hidden trends and subconscious themes. It was through this exercise that I discovered writing is a projection of the mind and that I could learn a lot about myself by reflecting on and distilling my belief system.

In mid-2024, I also started playing around with a bit more coding. It’s interesting to think that only 10 months ago, I basically couldn’t code. I came across an interesting essay from a guy that explores how we can map our writing with AI to see how we uniquely write and “stumble through latent space” (Writer Detection with LLM Latent Space Images.) This was pretty interesting to me at the time, because I was also coming to the realization that our writing is a projection of who we are and if you could map it, it could potentially offer valuable insights into our unique thought processes.

In my free time, I built an engine, Project Delta, that ingested my writings and mapped them in latent space with PCA analysis. It was just interesting to me at the time that you could see similar ideas clustering near similar beliefs and essays. As I sought to understand myself, maybe it was true that computers could also understand us. This seemed like a toy at the time and nothing more, but I was very interested in it.

The importance of this pre-history was two-fold:

I learned that writing is a projection of the mind

I learned that LMs have some capacity to understand our writing and possibly our mind by extension

The Start

I left a job ~10 months ago in June-ish 2024 with zero plan. It just felt that this was something I needed to do. My instincts were nudging me towards the importance of doing unlikely things. I wouldn’t have been able to articulate this at the time. I struggled to conform in a role that I’m sure many others would have loved to have, and would indeed be much better than me at. If the goal is to provide value that would not be provided “but for” me, then going my own way seemed like the right thing to do. Now, I had an intuitive sense that this venture creation model was exactly what I wanted to do with my life and makes sense to pursue directly.

Upskilling

There was a certain amount of upskilling required. AI was taking off. I’m no stranger to AI and the ventures I built in college were machine learning in some form, but I knew that in order to really do something great, you have to understand the technology well. You have to own the gray. No one will solve these problems for you.

The learning I actually had in college was that the shortage is always in good engineering. And people who understand the technical aspects of the problem to solve it. These people are rare and have many competing opportunities. The high-agency thing to do, I thought, would be to become the great engineer and CTO.

I started coding a lot more projects to get a hang of it. I also read textbooks on machine learning, including Deep Learning, by Ian Goodfellow. This provided me with a clear and solid understanding of machine learning, and not in a shallow way that most understand. By reading the theory, I actually knew how this shit worked. So when people talk about their business, I can see through its shallowness and know that there’s nothing actually innovative about it. It provided me with general principles that I outlined. I created these principles not for how to think about AI right now, but for how to think about it over the next 25 years. Humans aren’t great at internalizing exponential growth and abstract concepts like the NFLT, but by integrating them into my mental framework, I had given myself a proper lens through which I could view the world.

I find these unique lenses to be increasingly important and tied to the blue note and your zone of genius. You see the world through a lens that others do not.

Break

I also gave myself a bit of a break to return to Chicago and reconnect with friends & family. I’ve been mostly away from home ever since I graduated college. I went straight to New York and then to North Carolina. It was good to rekindle old relationships and helped me recoup my humanity. It helped me remember who I am before I threw myself into the west coast.

Iterations

I eventually found that the plan that made most sense was to launch my own fund. This would be my life’s work if I could make it work. These funds are only as good as their companies, however, so the focus should be on the first company.

To create that company, I wanted to keep an open mind and explore interests that might open doors to unknown-unknowns. I still was very interested in the projects that I was building earlier mapping ourselves through our writing. But I worked on many other projects that seemed interesting or promising. But I found myself returning to my old interests over and over, as if there was something about them that was personally important. Something that uniquely captured my instincts.

Moving to Berkeley

After making sure my finances were in order and the runway was defined, I went back to North Carolina, packed up my civic, and drove to Berkeley. I lived with Sam Schapiro, who was taking part in a program at Simons Institute for the Theory of Computing. I would attend many of these lectures.

This environment mimetically made my work quite theoretical at the time. Probably over-theoretical, but it really forced me to dive deeper into the technical details of machine learning. Similarly, there was a certain rigor in thought that was powerful for how I thought about my work. Interestingly, I noticed that even top minds of AI in academia were mostly interested in formalizing existing logic and had surprisingly large blind spots on applications of their work and what the future of AI will hold.

The Creative Act

In my time in San Francisco, there was a certain problem that I was working through in the back of my mind. As I was thinking about what drew me in about embeddings and my writing, I had a profound realization that formalized in a logical proof what exactly it was that I found captivating.

In my conversations with Sam, there was a moment of clarity in a discussion we were having about the concept of cathexes. Sam talked about how the human mind doesn’t just see concepts in a simple way. We subliminally have millions of individual cathexes that comprise concepts. So when I love dogs, I don’t just love dogs, I love “loyalty” and “cute” and “fur” and different cathexes that comprise my understanding of a dog.

This directly paralleled my interest in embedding concepts and my writing. Embedding my writing was capturing these individual characteristics and mini-concepts. I had also read a very profound and important paper out of Anthropic called “scaling monosemanticity,” that showed how deep learning models understand concepts, including those related to personality and patterns of human thought, which further formalized this logic.

With these realizations, it was a moment of clicking. It was a true creative act. While it took me months to hit this act of realization, it only took me a day for it to pour out of me into a single essay called General Personal Embeddings.

The point of this essay is really that AI maps complexity. Not only the complexity of the world, I argue, but also the complexity of the human mind. So when I am embedding my essays, they don’t just capture general concepts related to the contents, but also human patterns of thought that deep learning models have learned through their massive training process on human textual data.

Deep learning understands the world and us. This is a really big deal.

Not only does this have implications for how we understand ourselves as human beings, but it has important commercial applications as models understand each of us in greater and deeper nuance. We are exiting an off-ramp of the world where each company only understands us narrowly on their platforms and entering the on-ramp of a world where general models understand us deeply. Each AI application will require this understanding to not only act on the complexity of the world, but to understand and provide profoundly personal experiences to the individual interfacing with their software.

To this day, I don’t think many people have absorbed the importance of this. Even the writers of the Anthropic paper seem to not call out the profound implications of “personality features” being recognized as activation features. Even as I write this, if you look up general user embeddings or similar ideas online, my essay is one of the first links to pop up. I want to say that I am pioneering this field.

But in order to actually personalize these experiences, software needs to have access to our “personality embeddings.” At the time, this made logical sense from a first principles point of view. It made sense that there needed to be some infrastructure layer to plug into every AI application. I think this is still true, however, I hadn’t really ironed out the wrinkles in my argument at the time. The last two chapters are pretty misguided. It had to be something that could actually be used and engineered in practice. I was naive in what form that would take.

Stanford Hackathon – Bridging Theory and Practice

Once again, with this unique lens I could view software, I returned to the real world to test my ideas in the market.

The unique lens was simply that people are overly-entranced with next-word prediction. This next word prediction is powered by deep representation learning and the learned understanding of concepts, both worldly and those that capture our unique personalities and patterns of thought.

In the full spirit of the improvisational act, I went to a hackathon at Stanford Law School in Palo Alto. I went with nothing other than this unique lens and looked for unique applications for which to apply it. Many people entered the hackathon with existing projects that I felt were not authentically new or inspirational–they were mostly an extension of 2000s software. Furthermore, most people didn’t have the technical grounding that I found so important. With my innate taste and sense for this in people, I spoke with every person and every group that was formed. Mostly teams of 3-4 lawyers and engineers. None of them stood out to me as thinking for themselves.

Even without being a lawyer or an engineer, I chose to go alone in full spirit of nonconformity. I spoke with judges and heads of AI at law firms and iterated upon what problems exist and that could be solved through this unique lens. I found one in dispute resolution. There is a human aspect of disputes that can lead to escalation. You not only need to understand the law, you need to understand yourself and the human at the other side of the table to avoid blind spots and prevent escalations.

Even alone, and without a product that many others had been building for months, I built something on the spot, and still won my track. Non-conformity has value in a world of likely people doing likely things. This was a tidbit of validation from the market, but I was still missing a lot. This likely wouldn’t be the best application. This was more an act of a solution looking for a problem, which is a trap I’m trying to not fall into.

Around this time period, Sam also sent me a product he came across on Twitter/X called the Twitter Wordware Personality Test. It was roughly in line with what I wanted to build. It went viral as people love hearing about themselves and how they are unique. This was similar to my own need to build an application for understanding myself through my writing. Notably, the backend was also open-sourced.

Berkeley itself was an interesting and chaotic culture and has a spirit of ideological rebellion that remains from counter-cultural movements of history. It was cool, but I kind of had to get out of there. I wanted to be near the builders. This was instinctual, but I think the real subconscious reason was it felt like I was trapped in the world of ideas, and I needed to build something real. And San Francisco was the place of practical builders building real things.

Moving to San Francisco

I took the train over to San Francisco a couple times and went to some events. Aspects of the city I found beautiful. I wanted to be in Cerebral Valley. It retained a bit of ideological flair but it also had a certain pragmatism to it. It was more aligned with building things people want. In contrast with Palo Alto, it still feels like there is a bit too much noise and spikiness, but it may be that creative chaos and artistry that is so important for challenging the status quo if I am to hold irreverence and non-conformity on a pedestal.

External Validation from the Market

For months, I explored different problem spaces where this could be relevant. I thought about my background in connecting siloed data. I thought about my unique lens in which I understood the world. Would this be best suited for AI Applications? Something else? What are people building similar things? What are they missing? What inspiration can I draw from them? Balaji Srnivasan popularized the “idea maze.” What I was about to embark on was that exact journey of running into dead ends, back tracking, and iterating.

I came across a few competitors. It felt like they were still missing something. But the validation was helpful. Notably, they were in the personalized AI application space.

a16z put out an investment thesis for the “AI Brain” and how we live in our own context. This was directly aligned with my vision. AI applications need our context. They’ve invested in some companies doing something similar, but even they were missing what I thought to be important dimensions. Existing recommendation systems use shallow data to capture our behaviors. So if you connect to a person’s calendar, you can see what they are doing at 4PM and possibly gain insight into their behaviors through this. But what I think is more interesting is our deep human context, which I feel captures us more intimately. My writing stood as an example of this. Through my writing, you can understand my unique belief system. So it felt that the source of the data had to be a place in which we can capture our thoughts. And the use, to be determined, seemed like one where it could provide quantitative value.

I spoke with the CEO of Superlinked, who was doing something similar for embeddings in companies. Superlinked essentially offers an open-sourced framework for concatenating different data types into embeddings, including general embeddings it seems. They were pivoting to the e-commerce space, because they could more easily prove quantitative value. They could show lift. If you can immediately show value, the sale becomes easier. I could learn from them vicariously.

Other competitors seemed to be focused similarly on e-commerce with sign up friction that seemed to be problems. It also matters what context you provide. There was a sense that you needed to focus on applications where users also wanted personalization. The incentives had to be right to warrant a user choosing to plug their data/context in, given data compliance and permissioning requirements as well as product friction and user experience.

It was this immediate understanding that seemed to be the value. And it was the quantitative lift that seemed to be the way to bridge my abstract ideas into the world of simple and explainable practice. The important dimensions of consideration were this context, this quantitative value, this repeatability, user-desired personalization, and this simple-to-articulate value. My ideas are cool to me, but no one else cares. People need to understand what’s in it for them. It also seemed that this lent itself well into a network business.

My ideas so far were that general models understood us deeply. This would power profoundly personalized applications. I thought that it was these embeddings that were powerful. It is true, in theory, that embeddings are the cleanest way to capture individual traits and serve as a sort of clean data currency that can be tied to a unique user. It felt like if you could build a defensible business around this that it would be incredibly strong.

To recap, the validation that I got from the market was that general models could in fact be used for personalization for individuals. And more importantly that applications are possible and that people do pay for them.

I still wanted to keep my problem space open before falling into any local minimas. I still thought embeddings were the key, maybe mistakenly.

First Product Iterations

It seemed like in the world today, one powerful feature of general embeddings was that they don’t require a specific schema.

I went to an event held by Milvus, a vector database company, where they explained the use cases of these vectors in personalization, search, recommendation systems, etc. What is powerful about the walled gardens of today and indeed the big tech companies is they have so much data on people. Milvus’ developer advocate Stefan Webb talked about how these embeddings are put on a shelf and siloed within different divisions. They had tried to use contextual data, but the learning was that the embeddings are more powerful, so tabular data, however shallow, still outcompetes contextual data. In other words, who you follow and what you like holds more predictive power than the context of your tweets in understanding who you are.

So if this is true, perhaps there is a way to bridge these embeddings between companies, providing companies with much greater understanding of their users. You could theoretically extract and combine dating preferences from Tinder, movie preferences from Netflix, social preferences from Facebook, shopping preferences from Amazon, career preferences from LinkedIn, etc. into one global, general view of a person.

I was speaking to Jeff Zhang and some other researchers I met at Simons. They led me down a path of doing more research into autoencoders, contrastive learning, and other deep technical methods for how to conduct this information sharing.

The thesis was, perhaps if you can create a “translation layer” that translates embeddings within internal corporate silos or perhaps even across them, with proper authentication and permission from your users, perhaps you could engage in some form of information sharing.

Similarly, I discussed this with the CEO of Superlinked, and he held similar beliefs, but thought that they were step 10 in their product road map. They first needed to link internal data sets into user embeddings before they could bridge them across silos and companies. This was a helpful form of validation. Notably, even Superlinked struggles with the cold start problem.

I proposed a partnership that would use my product, Jean, to solve the cold start for each of these companies. After they were in Superlinked’s systems, we could start to build out a sharing protocol between companies that would enable sharing across a homogenous sub-network. I felt that I was getting somewhere. This directly paralleled some of my learnings on how to build a network business at Shaper.

I found that this is indeed technically feasible, however, extremely complex and costly to build. You would essentially need to build out models that have trained representations between models. So you need to learn how to translate Amazon’s embedding into Twitter’s embedding. It would likely require building a translation model into a general model first, then within that general model, adding and/or concatenating the results. As you can see, I fell further and further into a gigantic rabbit hole of academic complexity. It would take me years to understand this problem space completely, and to try to build it with it being unclear if it would actually work, and the ultimate problem of how to even sell it to large companies with long sales cycles.

Importantly, I’m not sure that I would really be able to do this data sharing without Superlinked. It felt like it would be too steep a hill to climb to build a breakthrough translation layer between companies. After it was built, it wouldn’t even be clear that there would be enough of a need for it. The partnership with Superlinked didn’t pan out and so I headed towards solving the cold start problem.

The learning here was that general models enable the transmission of understanding across systems but that the hurdles to create this would perhaps be too large.

Theses

These essentially comprised two theses.

General embedding models unlock data sharing between silos

Instant embeddings solve the cold start problem

This still didn’t really seem to stick anywhere when I talked to people about them though. If I cornered an engineer, perhaps they could see how it was feasibly possible to do so, but it just seemed way too far out there. It was possible I had fallen way too far into the world of ideas.

I architected and built some pretty complex software architectures. I figured that if you could build it, they would come. That’s not what happened.

At the time, I built an architecture that was an authentication protocol, where when a user signs up for a platform, they authenticate with their GitHub, LinkedIn, and Twitter/X, that built integrations with each of these platforms. After authenticating, it would embed their platform data into a vector database that could later be recalled by the company and thus solve the cold start problem.

This was problematic for a few reasons.

The authentication hurdle was pretty steep and it wasn’t clear companies would care enough

LinkedIn and others are pretty protective of their integrations and really limit the amount of access you can get to data.

It wasn’t really clear how much data I could access just by “embedding” someone’s data, when pulled into the platform. It may have been the case that it wouldn’t capture anything at all useful.

After really thinking about these problems, I was coming to the realization that embeddings, while cool to me, are really not the goal. The goal is understanding. That understanding for companies can come through context if properly used. The problem is you just don’t know if that context will be useful.

However, it was very helpful to have built this. It showed me how the flow would work in theory. And the very complex architectures that I had built would be helpful for how I thought about my later solutions.

There would need to be some sort of trusted backend that maintained data access. There would need to be some sort of API that would present itself as an endpoint to be called upon. In many ways, it is this journey of failure, iteration, and learning that is not only important for understanding the market, but also for understanding how to build things. This personal learning is required. You can’t just be the ideas guy. You have to learn how to build the damn thing and for it to work. Lines in the sand for product vision were getting thinner.