AI Memory: Pre-History

A comprehensive review (part 1/4)

See the full report here.

Since the publication of General Personal Embeddings, Irreverent has been focused on the general embedding space and how new systems will shape the future of software. Over the last 10 months, this space has evolved into a new sector called AI Memory. While a significant amount of talent and investment has gone into the optimization of LLMs, we believe that AI Memory exists as a relatively underexplored area of progress, for the simple fact:

“Bad model with good context > good model with bad context.” [Vectorize]

In building systems for consumers, developers, and enterprises, we sought out literature to catch up to the state-of-the-art. To our surprise, there have been no complete overviews written of the memory space. This exposition will aim to be the first comprehensive review.

But to just catch up to the frontier would not be enough. After familiarizing ourselves so deeply with the space, limitations of current technical architectures, market participants, and available solutions was clear. In order to truly understand memory, we must first forget it.

This paper will first conduct a brief pre-history of memory and what brought us to where we are today. It will be the first part in a 4 part series.

In future posts, we will explore current memory architectures, market participants, use cases, and the tradeoffs with different approaches. Lastly, we will look into the future of AI Memory, future use cases, market opportunities, and new innovations that will be required to move us forward.

Pre-History: The Path to AI Memory

ChatGPT

When OpenAI released ChatGPT on November 30, 2022, it quickly captured the public’s attention. It was incredible that a deceptively simple interface appeared to think as we do.

However, this product was not perfect. Users quickly noticed that ChatGPT forgot everything between sessions. Ask it to remember your preferences one day, and the next day you’d start from scratch.

How LLMs Actually Work: Databases, Not Brains

One large misconception often made by the public is that while Large Language Models (LLMs) seem very intelligent and “smart,” they are really more databases than they are brains. This is why LLMs often fail when doing simple operations of arithmetic. These products are not great at solving problems and thinking through new math, they are fundamentally built to parrot things they have been trained on.

A better heuristic for LLMs is as probabilistic databases of vector programs rather than reasoning entities [Chollet]. During training, these models encode and compress patterns with loss: how technical documentation is structured, how confident people write versus shy people, how to explain quantum physics at different levels, how poetry flows, how code debugging proceeds.

Activation Context

Without specific context, LLMs default to “average”. When tasked with generating an image of a male, the below image is generated. We can think of this person as the output of mashing together the face of billions of images it was trained on into the “average.”

For example, this is a ChatGPT generated image of the average male face.

Prompt: “Now generate an image of the average wisconsinite cheese loving packer fan”

It is only by introducing context on “wisconsinite” “cheese-loving” and “packer fan” that these feature dials are turned up and a program that resembles the combination of all of these factors generates this image. Notice how this program does not necessarily require you to ask for the jersey and “cheese head,” it triangulates what you are prompting for directionally.

LLM Memory is Limited

We can not say that LLMs don’t have memory at all. Clearly, these systems have some level of recall for conversations that fall within your chat window. But this is only a result of how the products we use were built.

Similar to how working memory for humans is around 7 items, LLMs have a working memory or “short-term” memory that only exists because we append prior messages to every new chat. So every time you send a new message, that message, along with all the others before it, are sent as a new prompt to the AI. But there are limits to working memory and LLMs as a whole.

The Three Core Limitations of LLM Recall

1. Statelessness

Every API call to an LLM is independent. The model retains nothing from previous interactions unless explicitly provided in the current context. This creates cascading problems:

Users must repeat background information constantly

Applications cannot learn from interaction patterns

Multi-session workflows require manual context management

Personalization demands extensive prompt engineering

Developers initially worked around this by storing conversation history and re-injecting it with each request. But this naive approach quickly hits context limits and becomes prohibitively expensive as conversations grow.

This is the most intuitive problem that most people understand. Until recently, these models could not remember across chats, sessions, and applications.

2. Training Cutoff

LLMs freeze at training time. GPT-4’s knowledge ends in April 2023. Claude 3.5’s knowledge ends in April 2024. Anything that happened after these dates—new research, current events, product updates, personal experiences—simply doesn’t exist in the model’s training data.

For generic knowledge work, this is manageable but inconvenient. For personal AI assistants or enterprise applications dealing with internal documents, it’s fatal. The model has no access to the information it needs to be useful.

3. Context Window Degradation

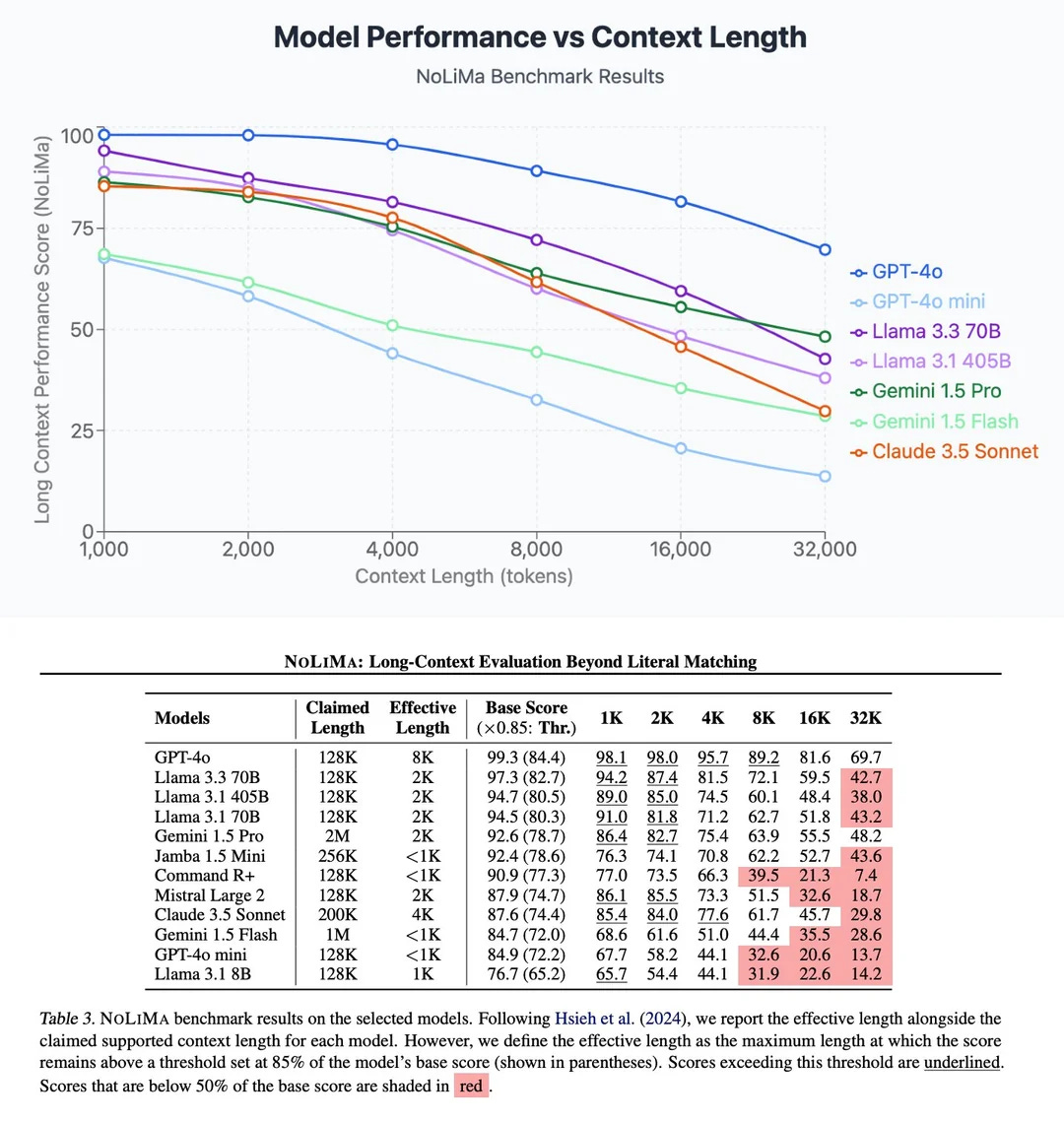

While context windows have expanded from 4K tokens (GPT-3) to 128K (GPT-4 Turbo) to 2M+ (Gemini 2.5), research consistently shows that performance degrades with context length. Historically, performance falls precipitously after only 32k tokens, even with advertisements of ever-extending context windows.

The “lost in the middle” problem: Models struggle to retrieve information from the middle of long contexts, even when that information is directly relevant

“Needle in haystack” failures: Success on benchmarks related to retrieval of specific information within a large wall of context are often inflated and performance suffers in most practical use cases.

Attention dilution: As context grows, the attention mechanism spreads activation across more tokens, weakening the signal from any particular piece of information

Latency and cost: Processing scales quadratically with context length—doubling context quadruples compute

NoLiMa: Long-Context Evaluation Beyond Literal Matching

Simply dumping everything into context isn’t a solution. The model drowns in noise.

The First Tool: Web Search as Memory

Before structured memory systems existed, the first “tool” that successfully extended LLM capabilities was web search. Even though most LLMs are trained on the Internet, the success of this tooling showcases the limitations inherent in training alone and the need to access context outside of the chat window.

[prompt → external information store + retrieval → context injection] became a normal flow.

Although web search isn’t read/write, Google’s web index was the closest semblance of a “memory” system for LLMs and soon became native to ChatGPT, Claude, and the other large models. Notably, if you wanted to add search into custom AI models, there were no immediately available solutions.

The disentanglement: Initially, web search was tightly coupled to ChatGPT. But within months it separated. Perplexity launched as standalone search-augmented AI, applications emerged with bespoke implementations, Brave launched an API that could be cheaply integrated into every LLM on the market, and eventually web search became available as infrastructure that any LLM could use.

This disentanglement happened because (1) developers wanted choice and (2) developers didn’t require the upfront implementation complexity and cost to train their own web search as they would an LLM. In the case of search, this became commoditized rather than a core product differentiator. The initial cost of development made LLMs prohibitively expensive but web search became commoditized.

Memory is not identical to web search. Implementations will vary widely. While we can’t expect memory systems to follow this exact path, we do anticipate the disentanglement of memory. Developers similarly want choice. However, the upfront cost is not quite as large as LLMs.

The Early Memory Attempts: RAG and JSON

In order to create effective AI systems and applications that were more useful than chat bots, LLMs needed radical innovation in how they could interact with the outside world.

While LLMs could now read from the internet, they could not access other data stores, such as a company’s internal documents. Constant hallucinations and poorly structured outputs also made it difficult for LLMs to call tools that require deterministic inputs. Knowing whether searching for new context would be helpful and what to search for became an operation that LLMs struggled to work with.

The Structured Output Problem

Early LLMs were not designed to produce or consume structured data reliably. Getting GPT-3 to output valid JSON quickly became a bottleneck in development. Models would hallucinate extra fields, break syntax with stray characters, or wrap JSON in conversational text (”Here’s the JSON you requested: {...}”).

This created a chicken-and-egg problem for memory systems: you needed structured outputs to store memories systematically, but the models couldn’t reliably produce them. Early developers resorted to:

Extensive prompt engineering with examples

Regex post-processing to extract JSON from conversational responses

Multiple retry loops when parsing failed

Temperature tuning to reduce creativity (and thus syntax errors)

The breakthrough came from targeted training. By mid-2023, OpenAI introduced function calling in GPT-3.5-turbo and GPT-4, where models were specifically fine-tuned to produce structured outputs for tool usage. Suddenly, getting reliable JSON clicked. The model had been trained to understand when it should output structured data versus conversational text. Anthropic’s Claude models, especially Claude 3 onwards, excelled at structured output and context processing.

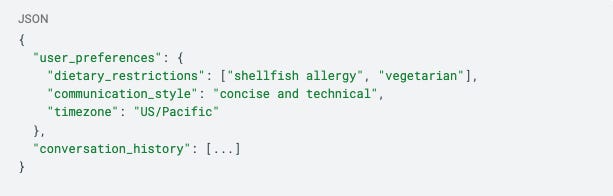

JSON-based memory patterns emerged from this capability, where an app may store user preferences and facts as structured data, inject them into the system prompt or context, and have the model reference them appropriately.

Early patterns looked like:

This worked for simple cases but revealed immediate limitations:

Scaled poorly as fact count grew

Required developers to decide what to store (no automatic memory formation)

Couldn’t capture nuanced information that didn’t fit neat key-value structures

Rigid schemas force information into predetermined categories, preventing models from using generalized pattern matching or intelligent actions

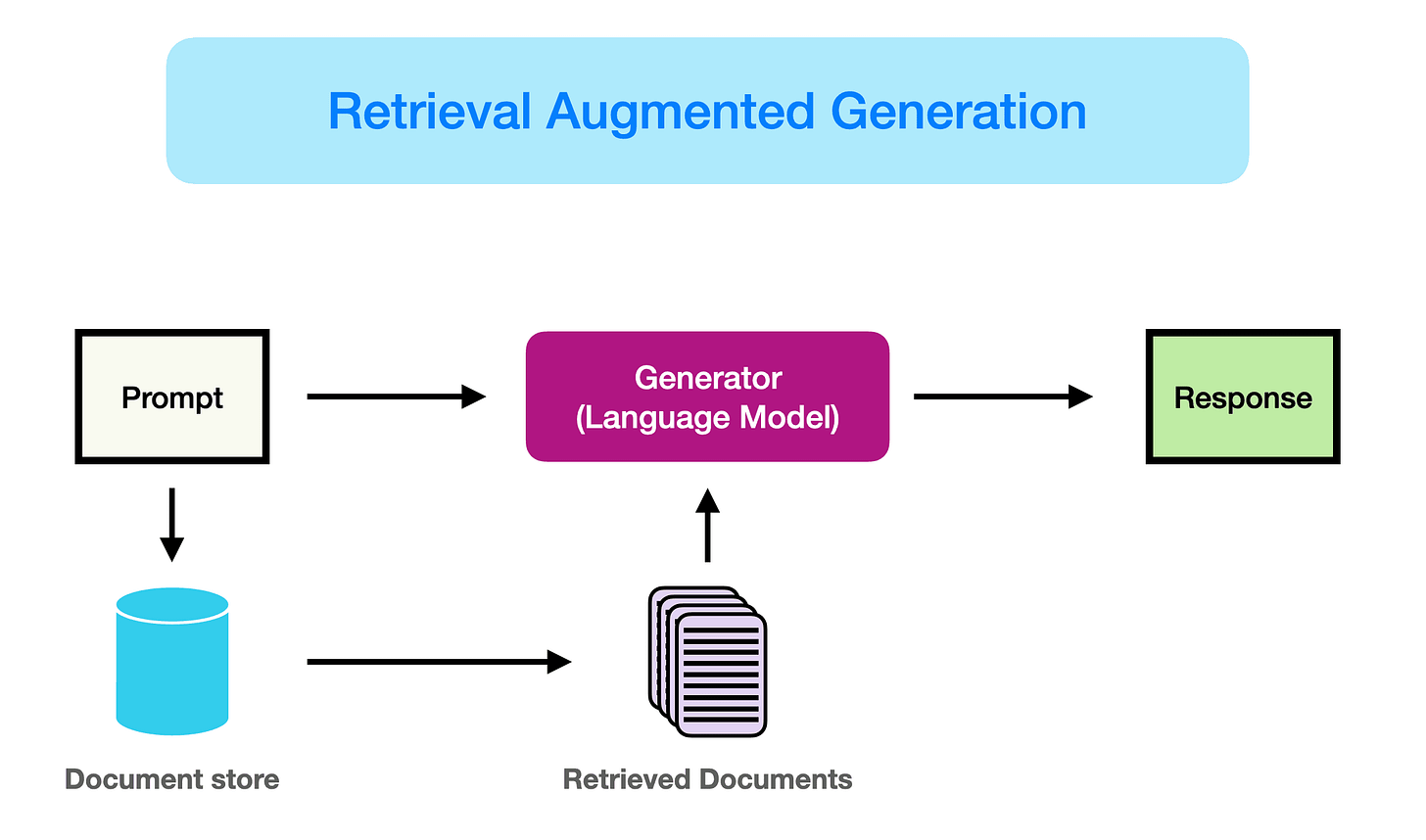

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) emerged as the more sophisticated paradigm by early 2023. The architecture was conceptually simple:

Convert documents/memories into vector embeddings

Store embeddings in a vector database

When a query arrives, find semantically similar embeddings

Inject retrieved text into the prompt alongside the query

Implementing RAG well required solving multiple non-trivial problems. For instance, how do you know when to pull documents at all? How many? Often, these systems hurt performance by injecting irrelevant or distracting context. Some other issues.

Chunking: How do you split documents so embeddings are meaningful? How do you maintain relationships across chunks?

Embedding quality: Which embedding model captures semantic similarity best?

Retrieval tuning: How many results to retrieve? What similarity threshold?

Context packing: How to format retrieved information so models use it effectively?

LlamaIndex and LangChain built entire businesses on abstracting these decisions. Within months, implementing basic RAG went from requiring deep ML expertise to being achievable in an afternoon with a few API calls. But the ease of implementation masked ongoing challenges in retrieval quality and context utilization.

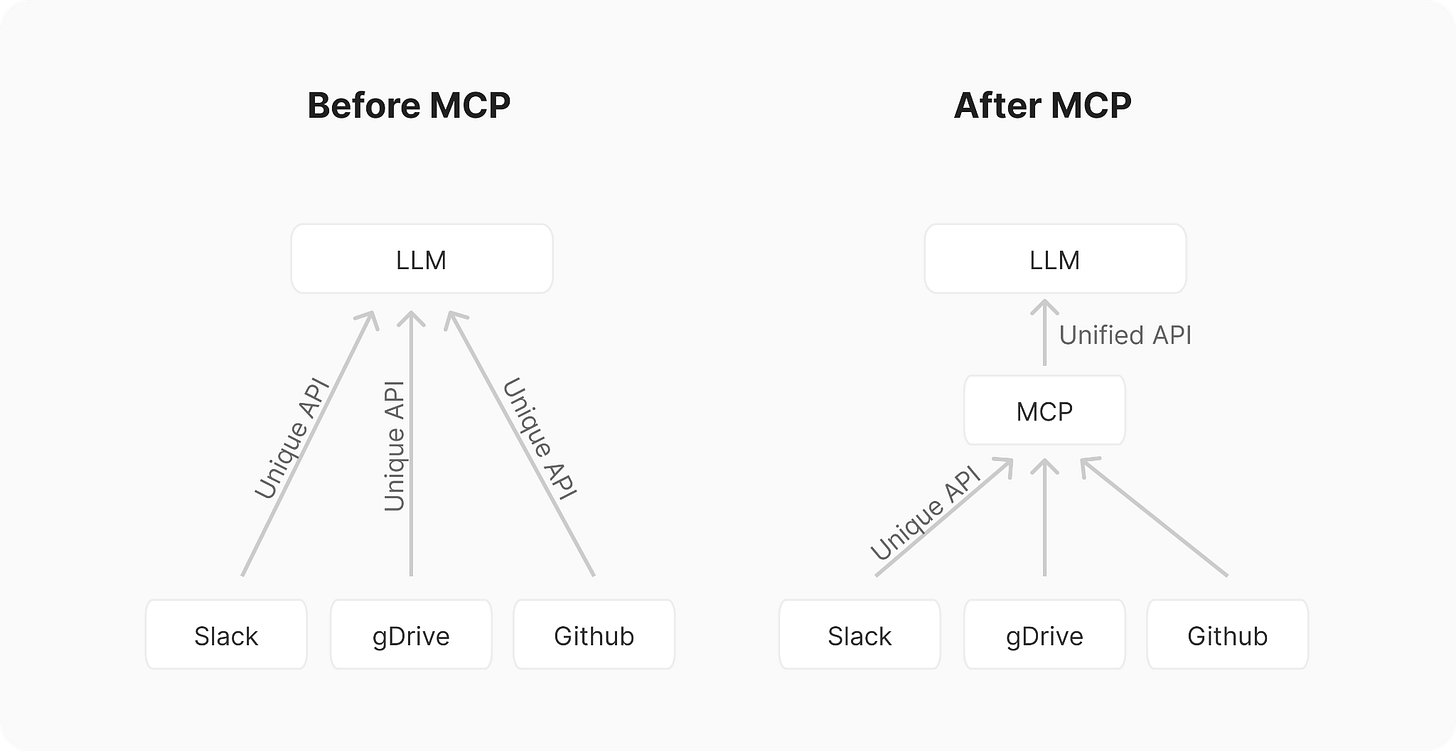

Tool calling and MCP emerged as another early pattern. Rather than trying to put everything in context upfront, give models the ability to request information on demand. This required yet another training breakthrough: models needed to learn when to call tools, how to format tool requests, and how to incorporate tool responses into their reasoning. MCP also promised to standardize the connection between all tools, so developers weren’t forced to develop connectors for each.

Function calling became standard by late 2023, but effective tool use remained challenging. Models would:

Call tools unnecessarily (wasting latency)

Fail to call tools when needed (missing critical information)

Misinterpret tool results

Get stuck in loops calling the same tool repeatedly

M x N complexity for each tool requiring its own integration

Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP), announced in November 2024, attempted to standardize tool calling for context retrieval.

While many focused on MCP’s importance in reducing M x N integration complexity, the subtle theme of intelligent tool calling was actually more important. It is not enough to be able to call tools. You actually have to build systems that know when to use what, how to use each tool, and then get rid of polluting context that distracts the AI from completing its task, which brings us to context engineering.

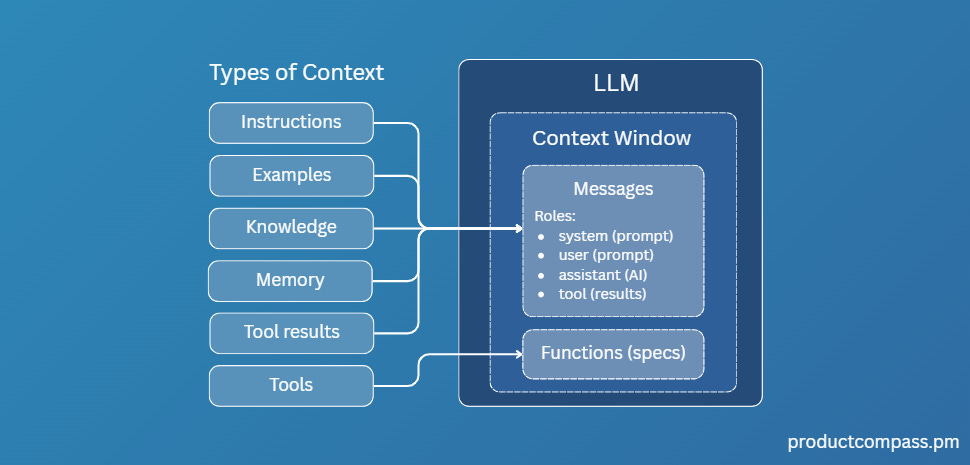

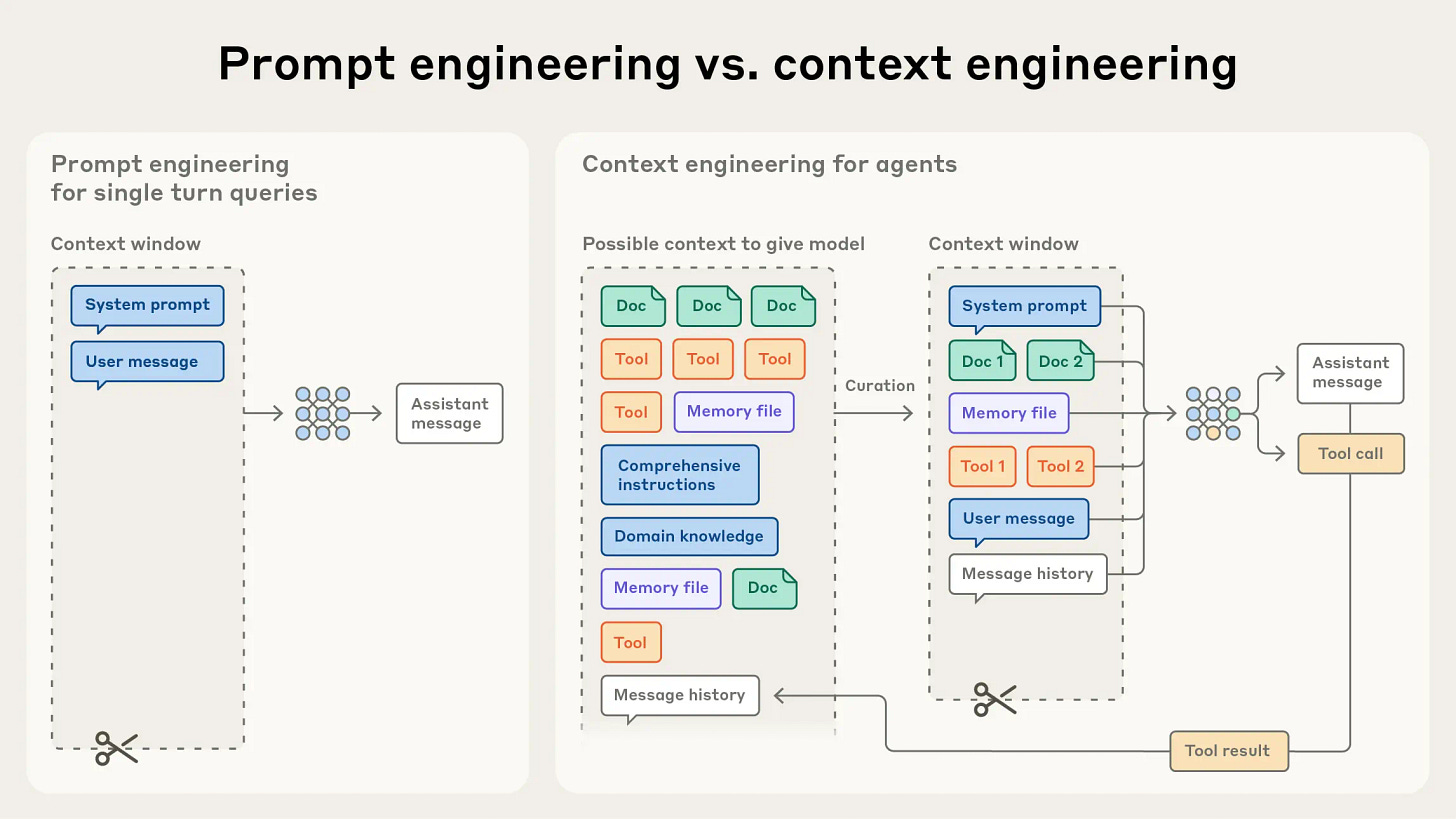

The Emergence of Context Engineering

Coined by Shopify CEO, Tobias Lütke, “context engineering” is the practice of dynamically constructing and managing what information gets injected into the model’s context window. This practice can really be summed up into “right context, right time.” Sounds easy, but it is a dynamic engineering problem involving the orchestration of many moving parts with resurfacing constraints around latency.

Context engineering is fundamentally a resource allocation problem: with limited tokens available, what information deserves inclusion? Every retrieved memory, every tool call, every piece of injected context consumes budget that could be spent elsewhere. For users of AI systems, we don’t like to wait. We want it to “just work” and fast.

While the LLM is the central nervous system of AI. Memory and context management play a significant role in creating effective AI systems. Which brings us back to our pithy quote from the introduction that,

“Bad model with good context > good model with bad context.” [Vectorize]

Context engineering became the grown up version of prompt engineering:

Prompt engineering (2022-2024): Crafting the perfect static instructions, write once, use repeatedly

Context engineering (2025-present): Dynamic information assembly, what to retrieve, how much, when, in what order, and how to formatted the output

Modern Memory

By mid-2024, the technical building blocks existed. Storage, JSON storage, function calling and MCP, and context engineering became household names in engineering AI systems. But making them work together remained a challenge. Each component introduced failure modes that compounded:

RAG systems retrieved irrelevant documents that polluted context

Function calling added latency while models decided whether to search

JSON structures either oversimplified complex information or became unwieldy

Context engineering required constant tuning as models and use cases evolved

By late 2024, the fundamental architecture of external storage + retrieval + context injection solidified. The sophistication varies wildly, from simple vector databases to multi-layered memory systems, but this basic pattern has held.

This standardization marked an inflection point. As we’ll see in the following sections, this opened the door to market segmentation and varied solutions.

—

Part 1 of a 4 part series on AI memory.

If you are interested in implementing memory systems, reach out to Jean.

— jonathan@jeanmemory.com