Business isn’t taught; it’s learned by testing in the market—so a real skill is knowing when to build and when to think.

Sundays

I’ve come to really enjoy my Sundays, which I usually dedicate to thinking. This feels like an odd thing to say, but it’s clear to me that there are different types of thinking.

I’ve written before about the value of an education in “business.” I don’t believe in such a degree, because business is simply the process of going from A → B. There are two parts of this process. First, you need to know you’re at A and define what B is and why you need to go there. Second, you need to execute this strategy.

This planning makes sense. It also makes sense that the majority of time and focus should be spent working on getting to B. But time should be spent planning to make sure you’re on track, and that’s why I need Sundays. Often, B is fuzzy, and it’s by moving and learning that it becomes more clear.

Three critical questions that arise when building a business are “what?” “why?” and “how?” What are we building, why are we building it, and how are we going to build it?

It is incredibly important to make sure you are working on the right thing before expending your limited time, focus, and energy on it.

The Means and the End

In most of our upbringing, we are taught to solve for B, which is defined by someone else. When you are an employee in a hierarchical institution, you are taught to solve for B as defined by your manager. That is the nature of how an organization can scale. Your senior management defines the what and why, and you then hire competent people to fill in the gaps to how to execute upon the defined vision. Someone who can clearly articulate a “what” and “why” can be more valuable than someone who can execute perfectly.

Over the course of my life, I’ve become increasingly confident that you must also be in the trenches to earn the “what” and “why” and that these modes of thinking must be coordinated.

In theory, it sounds nice to be able to define B and then let other people figure out the messy middle, but the world requires more from its leaders. In banking, many people flatly hate MBA associates, because they don’t know how to practically do the job that analysts had to learn.

This is even true in mathematics, highly regarded as a theoretical field by nature:

“In short, there is no royal road to mathematics; to get to the “post-rigorous” stage in which your intuition matches well with what one can establish rigorously, one has to first invest real effort in learning and relearning the field, learning the strengths and weaknesses of tools, learning what else is going on in mathematics, learning how to solve problems rigorously, and answering lots of dumb questions, and so forth. This all requires hard work.” - Terence Tao (Work Hard).

It’s clear the practical nature of the job has an impact on the theoretical nature. An abstraction at the next layer of a corporate hierarchy is composed of the previous layer’s tasks and responsibilities. You can’t skip layers of abstraction without understanding the previous one.

Theory and Practice

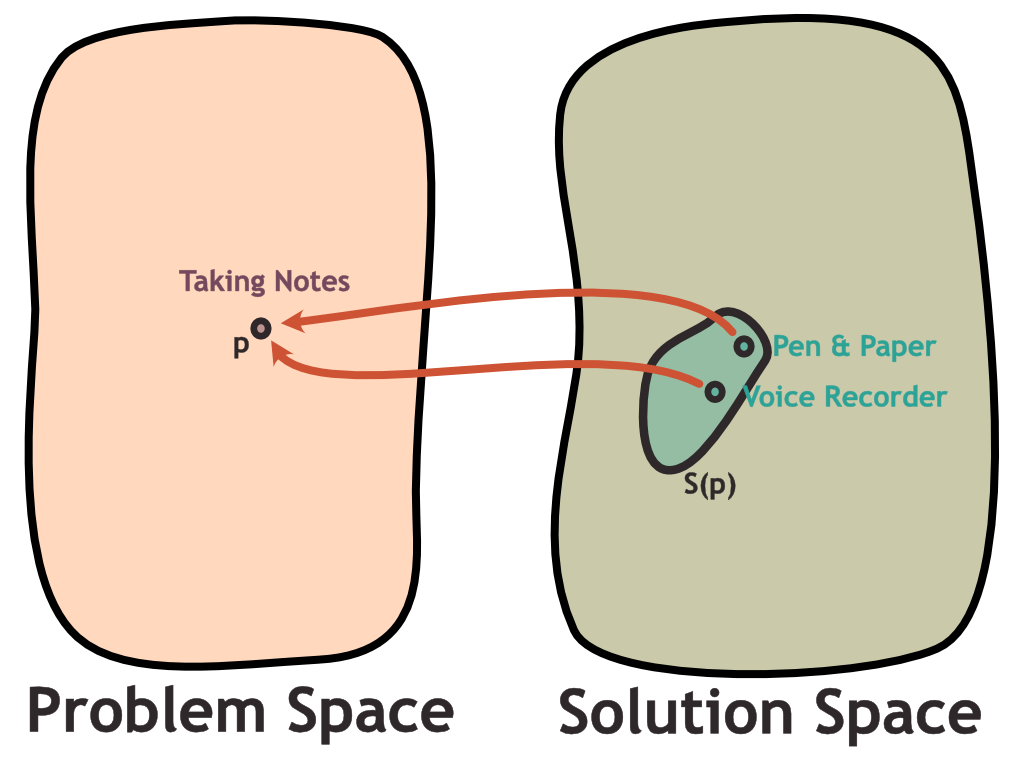

This dance straddling theory and practice is at least in part due to the separation between problem space p and solution space S(p).

The problem and solution maps are separate concerns, but they are not completely independent. You may be locked in on a problem (“what” and “why”) you’d like to solve, but what if the solution space (“how”) isn’t there yet? We would love to go back in time and undo our mistakes, but it is difficult to engineer a time machine. This is a simple example of a 2-dimensional coordination problem. There are other dimensions to consider as well.

Maybe you can align problem space p with solution space S(p), but it turns out that the market and FDA don’t like you and regulatory space R(p) is a dead end and market space M(p) isn’t a strong enough headwind.

We will dive deeper into this in a later section, but maybe the infrastructure I(p) isn’t there yet, which is necessary to build your solution. What then, do you wait it out?

Problems as Mountains to Climb

Product-Market Fit is not only the result of determining point B within problem space p, but it is the process of mapping and coordinating the other dimensions and then solving the problem in practice.

Many of the problems are apparent themselves and may have even glared industries in the face for decades, so the more important question is sometimes “why now?”

Tao also discusses how problems may at times be as insurmountable as a large mountain, even by the greatest mathematicians, and it may require waiting years until the problem space has been chipped away by others until there is a viable path to the top.

The Fermi Paradox of Startups and Premature Markets

If I think about the problems I am interested in solving, I am frankly surprised that the market hasn’t caught up fully and that there are few people solving them.

In fact, I’ve been pretty taken aback by the smallness of our world. How I can speak with someone in London who is interested in a problem that is somewhat similar 6 months ago and then run into them in a conference on the topic in San Francisco, and then my roommate also knows them, and then meet people that I’ve come across on Reddit boards who have posted my product on their website. This world is so small when you get closer to the bleeding edge of something niche that you are authentically interested in.

I’m coining this the Startup Fermi Paradox: you spot an unmistakable opportunity, yet no startups seem to exist. The absence isn’t because motivated people are missing; it’s because real constraints—capital, engineering talent, regulatory friction, timing—still block a viable path. Until those stars align, even the most compelling ideas sit dormant.

Each person may also view problem space p with a subtly different lens and have a unique angle to solve it in solution space S(p) in a different market. Each alien out there is inherently different and you can learn from their approaches.

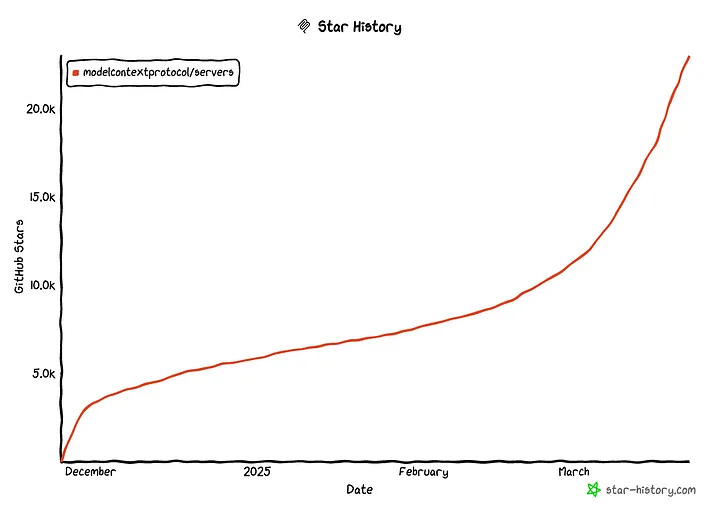

But over time, these blockers get unlocked, and the recent success of MCP is a great example of this.

MCP

The conference that I met this other young founder in person at was a recent conference at GitHub’s office here in San Francisco on the topic of MCP (model context protocol) that Anthropic released in November 2024.

I’m simply not used to being in a space that is growing like this. It feels surreal. I’m not sure how one calibrates a company or even themselves to operate in this growth.

Many people get bogged down in the details of MCP’s features, but what I think MCP represents is simply distribution and attention to external context and tooling.

This is one of the many solution spaces that I was forced to align in my own product. Seemingly, Anthropic created an infrastructure layer that was reasonably good enough to take that problem off my hands, relieving some of the burden of building this damn thing in a distributable way. However, while this is great, it also does the same for others.

The Flurry

What happened when this I(p) space got sorted out is it felt like the floodgates opened for a large number of startups. One of the stars aligned that enabled many solutions in the market to come to life.

Seeing activity unlocked like this also makes you realize something else. As you see people flood into the space, you see what was once a less efficient market with maybe 5 imperfect people working on a problem becomes an efficient market with 100s of people solving different parts of the problem.

Unlocks

What this flurry represents is an unlock.

The activity has been palpable and quite intimidating. The reason for this is while it has felt like I’ve been alone in my problem space (like us and the aliens), it shows me that competitors are out there and that the market catches up to your instincts. Like Terence Tao solving math problems, there are just a few more stars that need to be aligned before this mountain is viable to climb. And the most important lesson in all of this is the same as in economics and financial markets,

“Things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could.”

So you need to be ready to capitalize. From this experience, I have learned that you need to be flexible to account for changes in the market, and be on call ready to shift gears at a moment's notice. But you still need to be leaning into a long-term perspective to be prepared to catch lightning in a bottle when it strikes.

Resource Scarcity’s Impact on Strategy and Timing

This dance between theory and practice takes another form across the scales of time and resources. What I am describing is the dance between what is ideal and what is feasible. And much of this comes down to the time you have and the money in your bank.

With infinite resources and time, you can create the ideal product. However, with limited time and resources, you must lean into the present. Especially in network businesses, you need to focus on short-term (Short Term Success).

You are burning cash to accelerate your solution to the front of the market. You need to get the timing right. Perhaps if you wait 6 months, your solution will be built by someone else. Or maybe it will finally be achievable with your cash balance.

Money can’t buy time. Money also cannot buy clarity of vision. I sometimes think clarity of vision is the most important thing to have in startups. With a clear vision of what the product should be, you can be fast and ahead of the crowd, outcompeting even large companies. Silicon Valley relies on this vision asymmetry in its big bets on founders. I mostly think that money is a byproduct of clarity of vision.

Long-Term vs Short-Term

In the balance of problems now and planning for the future, there is a middle ground you need to strike.

You have to be stubborn on long-term vision, but flexible and scrappy on how to wedge in and learn today. There may be different angles to approach your problem from, each with different characteristics. You need to pick the best one and constantly reevaluate.

Being clear on long-term vision sounds easy, but it’s not. The world is not rational and it unfolds in weird ways. The introduction of MCP completely changes how I view my own product. But if you have a robust guiding vision, it leaves room for the messy means to make it to your final destination (B).

The problem with a long-term, theoretical approach is that it is difficult to measure. If you are building something for people in 2050, how can you even know what 2050 will look like? The easiest thing is to have long-term hypotheses, but quickly test and iterate in the market.

The learning cycle is too long in your own head. But customers will tell you exactly what they want. In this sense, even if you have grander ambitions long-term, it may make sense to just focus on short-term growth and learning.

Looking back on it, I was forced to build some of what is now a very complicated protocol in MCP into my product, way overcomplicating things and making the sell much harder.

Focus on Rate of Learning

It feels weird for work to just be done to learn. This sounds odd to say as a company with a focus on making money, but I think it’s true. If you have two founders, one that spends the early days mapping out the market and learning, and the other that builds a product for the first person he meets, it makes sense to me that you’d want to bet on the one learning in the long-term.

I’ve noticed that people here in Silicon Valley like to ask the question, “how far along are you?” They are obviously trying to suss out what stage you are in as a company and frankly it feels like they’re trying to assess your worth. It’s a valid question, but I do think that it masks that learning, however intangible and ambiguous, is often a much more valuable metric in the early days of a company.

MCP

So with all that said, the next essay will evaluate the recent rise of MCP and what it really means for AI, before using this new understanding to reevaluate Jean’s course.

After the essay on MCP, we will again ask the questions and cite our core vision.

“What are we building, why are we building it, and how are we going to build it?”

Conclusion (written by o3)

Building from A → B is less a straight line than a pulse: think, act, learn, repeat. The market rewards founders who keep that cadence—anchoring long-term vision while pivoting the moment an “unlock” (like MCP) removes a hidden constraint. The Startup Fermi Paradox reminds us that empty spaces aren’t empty; they’re simply waiting for timing, tooling, or talent to click into place. Our task is to stay close enough to the frontier to sense those clicks, disciplined enough to preserve cash and clarity, and humble enough to measure progress in learning velocity, not vanity metrics. With that posture, every Sunday reflection sharpens the map, every Monday sprint moves the needle, and the journey from A to B becomes inevitable—even if the path still looks invisible to everyone else.

Was just thinking about something similar recently. Slim molds and cosmic web design shows us how expansion begins with the fastest route to resources. Yet what happens when most jump in to pursue the same energy source?

A: Those left behind look for another place overlooked providing what's needed.